Fancy C-3PO doing your chores, or something more robotic?

Robots demonstrating their capabilities proliferate at technology conferences. On a recent visit to the Mobile World Congress in Barcelona, one handed me a morning coffee. Its crane-like arm ended with a pincer that deftly carried a cup to a machine to fill with liquid, then passed it, spill-free, to my hand.

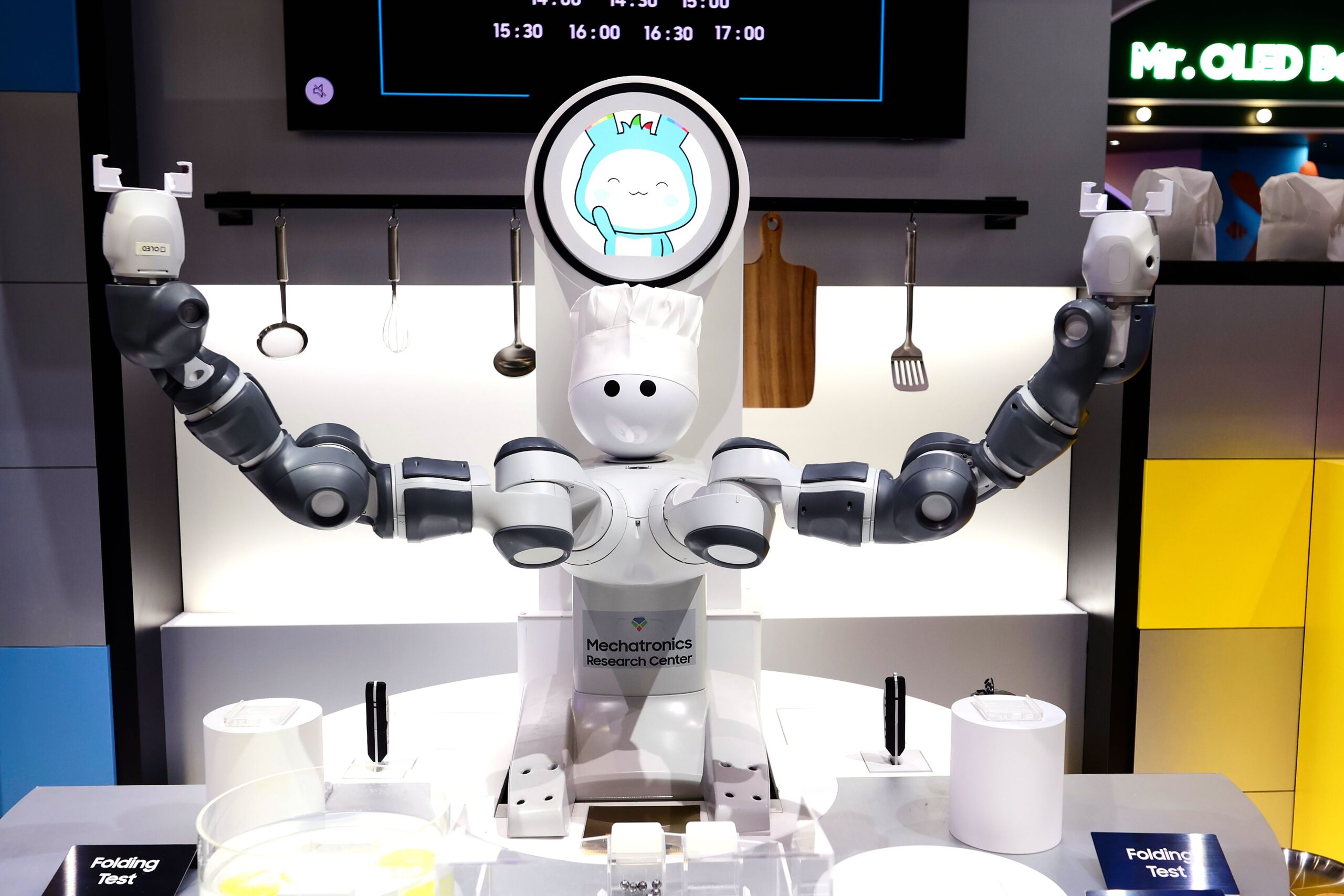

While this was going on in one corner, a set of crane arms performed keyhole surgery on a fake patient in another. Meanwhile, a 5ft-high rectangle with a wraparound screen glided about the conference centre, offering information to lost delegates, making reassuringly robotic beeps as it did so.

None of these robots looked like people. Yet the push for those that do, referred to as “humanoids”, is increasing. Think C-3PO from Star Wars.

One company in pursuit of this is Figure, in Silicon Valley, which is building human-like robots powered by artificial intelligence. It raised $675 million this year from OpenAI, the developer of ChatGPT, and Nvidia, among others, valuing it at $2.6 billion.

What are these robots for? Figure’s heady vision is to help solve the labour shortage and replace dangerous jobs with technology. The argument goes that the world is designed for the human form, so robots would be best designed that way too.

Agility Robotics, a developer backed by Amazon, is building robots that move like a person to fit “a world made for people”. Elon Musk, the owner of Tesla, has also been working to build a human-like robot named Optimus. The tycoon predicted in January that there could be a billion of them walking the Earth within the next 20 years.

There has long been a fascination with humanoids and a desire to create robots in our likeness. An early example was Eric, a robot designed and built in England in 1928 that looks a bit like The Tin Man from The Wizard of Oz.

Recreated for the Science Museum in 2016, he could stand, bow, give a four-minute speech and answer up to 60 questions.

A recent report from Goldman Sachs, the Wall Street investment bank, said the market for humanoid robots would reach $38 billion by 2035, as they helped with everything from folding washing to handling hazardous waste.

While they are certainly striking to look at, not everyone believes the hype. Look more closely at the demonstrations, robotics experts say, and there is a very long way to go before humanoids can approach the capabilities of a human, and they question whether the human form is the most useful.

Engineered Arts in Falmouth has been building humanoid robots since 2004. Far from replacing human labour, these incredibly realistic bots are popular for entertainment, such as in theme parks.

Will Jackson, 59, chief executive, says humanoids work best when they are interacting with people. Form, he argues, should always follow function, so he can see uses in healthcare, in care homes and in hospitality. For all other automated tasks, he queries: “Why be human when you can be superhuman? Why have two arms when you can have eight?”

James Matthews, 41, chief executive of Ocado Technology, agrees that it comes down to the problem you are trying to solve. Far from being filled with humanoids, Ocado’s bespoke robotics warehouses are dedicated to machines that do specific jobs, such as a hand that can both pick up a peach without bruising it and grasp a heavy wine bottle.

There is no doubt that advances in AI will transform robotics. The British company Opteran, a spin-out of the University of Sheffield, is looking at how algorithms in insect brains can be applied to autonomous machines. David Rajan, 57, chief executive, said the company will move on to rats and mice in the next five to ten years. He added: “The challenge is not the form factor, but how to navigate the real world.”

On Tuesday, Yann LeCun, 63, chief AI scientist at Meta and a global leader in the field, explained: “At present,when we compare the learning abilities of our machines to what animals and humans can do, they don’t stack up.

“How is it that we don’t have domestic robots that can do all the chores? It’s not because we don’t know how to build those robots; it’s because we don’t know how to make them smart enough.”

Rather than having two arms, two legs and a head, the brain will be the key to creating human-like robots.

Katie Prescott is Technology Business Editor of The Times

Post Comment